Horner's Syndrome

content of this page

1- Introduction

2- Causes

3- Pathophysiology

4- Clinical Features

5- Investigations And Lab Results

6- Complications

7- Treatment

Introduction

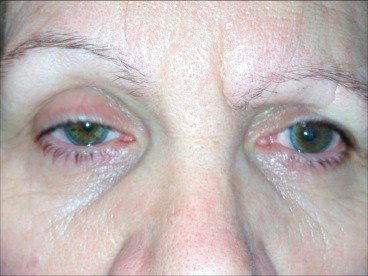

Horner’s syndrome is a neuro-ophthalmologic condition resulting from disruption of the sympathetic nerve supply to the eye and face. It presents with a characteristic triad of ptosis (drooping of the eyelid), miosis (constricted pupil), and anhidrosis (loss of sweating) on the affected side. This syndrome is an important localising sign in neurology and may signal underlying pathology anywhere along the sympathetic chain—from the hypothalamus to the upper thoracic spinal cord and beyond.

Causes

1. Central Causes (First-Order Neuron)

Lesions affecting the hypothalamus or brainstem:

Stroke (especially lateral medullary syndrome / Wallenberg syndrome)

→ Ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome with ataxia, vertigo, and sensory lossTumours or demyelination (e.g. brainstem glioma, multiple sclerosis)

Syringomyelia (central cord lesion)

2. Preganglionic Causes (Second-Order Neuron)

Lesions in the spinal cord or thoracic outlet:

Pancoast tumour (apical lung tumour invading sympathetic chain)

Neck trauma or surgery (e.g. thyroid or carotid surgery)

Cervical rib or thoracic outlet syndrome

Brachial plexus injury

3. Postganglionic Causes (Third-Order Neuron)

Lesions involving the superior cervical ganglion or carotid artery:

Carotid artery dissection

→ Painful Horner’s syndrome with risk of strokeCluster headache

→ May be associated with transient Horner features during attacksCavernous sinus lesion or internal carotid aneurysm

Basal skull tumours (e.g. nasopharyngeal carcinoma)

Congenital Horner’s syndrome may be due to birth trauma; often presents with heterochromia (difference in iris colour due to disrupted sympathetic stimulation of melanin synthesis during development)

Pathophysiology

Horner’s syndrome occurs due to disruption of the oculosympathetic pathway, which innervates the eye and surrounding facial structures. This sympathetic pathway consists of a three-neuron chain, and interruption at any point leads to the characteristic signs: ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis.

The Oculosympathetic Pathway

First-order neuron (Central neuron):

Originates in the posterolateral hypothalamus

Descends through the brainstem (midbrain → pons → medulla)

Terminates at the ciliospinal centre of Budge (spinal cord segments C8–T2)

Second-order neuron (Preganglionic):

Exits the spinal cord at T1

Travels over the apex of the lung

Ascends in the sympathetic chain

Synapses in the superior cervical ganglion at the level of the bifurcation of the common carotid artery

Third-order neuron (Postganglionic):

Follows the internal carotid artery into the skull

Travels through the cavernous sinus

Joins the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (V1)

Innervates:

Dilator pupillae muscle (pupil dilation)

Superior tarsal (Müller’s) muscle (eyelid elevation)

Sweat glands of the face and forehead

Result of Lesions:

Miosis: Loss of sympathetic innervation leads to unopposed parasympathetic tone → pupil constriction.

Ptosis: Weakness of Müller’s muscle → mild drooping of upper eyelid.

Anhidrosis: Loss of sympathetic supply to sweat glands → decreased or absent sweating (may be limited or widespread depending on lesion location).

Apparent enophthalmos (pseudo-enophthalmos): Eyeball appears sunken due to ptosis.

Clinical Features

Classic Triad:

The hallmark signs are unilateral and result from sympathetic pathway disruption:

Ptosis

Mild drooping of the upper eyelid

Due to paralysis of the superior tarsal (Müller’s) muscle, not the levator palpebrae (which is innervated by CN III)

Miosis

Constricted pupil on the affected side

More apparent in dim light (where the normal pupil dilates but the affected one does not)

Anhidrosis

Loss of sweating on the ipsilateral side of the face

May be limited (postganglionic lesions) or widespread (central or preganglionic lesions)

Additional Features:

Apparent enophthalmos

The eye may appear sunken due to ptosis (pseudo-enophthalmos)

Iris heterochromia (in congenital cases)

A lighter iris on the affected side due to reduced sympathetic stimulation during development

Seen especially if Horner’s occurs in infancy

Preserved visual acuity and pupillary reflexes

Light reflex and accommodation are normal since they are parasympathetic

Examination Tips:

Compare both pupils in a dark room – asymmetry will be more prominent

Observe for asymmetry in eyelid height

Feel for skin dryness on the affected side (loss of sweating)

Check for associated neurological signs, such as:

Facial sensory loss (if associated with trigeminal nerve involvement)

Limb ataxia (in brainstem lesions like lateral medullary syndrome)

Neck trauma or scars (suggesting carotid dissection or surgical injury)

Investigations And Lab Results

Clinical Recognition:

Diagnosis is made based on the classic triad of:

-

Ptosis (mild eyelid droop from Müller’s muscle weakness)

-

Miosis (constricted pupil with dilation lag in darkness)

-

Anhidrosis (loss of sweating on the affected side of the face)

A detailed neurological and general physical examination helps detect associated findings that may suggest the location of the lesion (e.g. limb weakness, ataxia, arm pain, headache).

Imaging Based on Presentation:

Neck pain or headache

-

Suggests carotid artery dissection

-

Perform CT angiography or MR angiography of the neck vessels

Arm pain, weakness, or history of smoking

-

Suggests apical lung lesion or Pancoast tumour

-

Order MRI or CT of the chest and brachial plexus

Brainstem or spinal cord signs (e.g. vertigo, dysphagia, limb ataxia, sensory changes)

-

Indicates central causes such as lateral medullary syndrome, demyelination, or tumour

-

Perform MRI of the brain and cervical spine

Clinical Localisation:

Lesion site can be narrowed using associated findings:

-

Central lesions: Accompanying brainstem signs (e.g. stroke, MS)

-

Preganglionic lesions: Signs of thoracic or apical pathology (e.g. Pancoast tumour)

-

Postganglionic lesions: Isolated Horner’s or associated with headache (e.g. carotid dissection)

Additional Workup:

Depending on suspected underlying cause:

-

Chest imaging for suspected lung malignancy

-

Autoimmune and inflammatory markers for demyelinating disease

-

Carotid imaging for dissection

-

Full neurological examination to assess for brainstem or spinal pathology

Complications

Underlying serious pathology

Since Horner’s Syndrome often results from damage along the sympathetic pathway, it may indicate serious conditions such as:Pancoast tumor (lung apex tumor)

Carotid artery dissection

Brainstem stroke or tumor

Spinal cord lesions

Permanent ptosis and miosis

If the underlying cause is not treated promptly, the ptosis (drooping eyelid) and miosis (constricted pupil) may become permanent, affecting appearance and sometimes vision.Anhidrosis complications

Loss of sweating on the affected side of the face can lead to:Dry skin

Potential risk of overheating in that area

Visual disturbance

Though usually mild, ptosis may impair the visual field in some cases.Psychological impact

Chronic facial asymmetry and eye symptoms can affect the patient’s self-esteem and quality of life.

Treatment

Treatment of Horner’s Syndrome primarily focuses on addressing the underlying cause, since Horner’s itself is a sign of sympathetic pathway disruption rather than a standalone disease. Here’s a breakdown:

1. Treat the underlying cause

Tumors (e.g., Pancoast tumor): Surgical removal, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy as appropriate.

Carotid artery dissection: Anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy, sometimes surgery.

Brainstem or spinal cord lesions: Neurosurgical intervention, radiation, or medical management depending on cause.

Infections or inflammatory causes: Appropriate antimicrobial or immunosuppressive treatment.

2. Symptomatic management

There is no specific treatment for the signs of Horner’s syndrome (ptosis, miosis).

Ptosis can sometimes be improved with surgical correction or ptosis crutches in glasses if it affects vision.

Cosmetic concerns can be addressed but are not medically necessary.

3. Monitoring and follow-up

Regular monitoring to check for progression or resolution of symptoms after treating the underlying cause.

Imaging and clinical follow-up to ensure no new pathology arises.