Peptic ulcer

Content of This Page

1- Introduction

2- Causes

3- Pathophysiology

4- Signs & Symptoms

5- Types of Peptic Ulcer

6- Risk Factors

7- Investigations & Lab Results

8- Complications

9- Treatment

Introduction

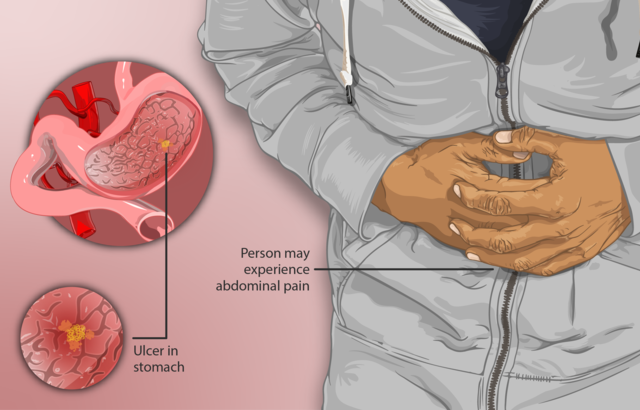

Peptic Ulcer is a break or sore in the mucosal lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or the duodenum (duodenal ulcer), caused by an imbalance between aggressive factors like gastric acid and pepsin and defensive mechanisms such as the mucus-bicarbonate barrier, prostaglandins, and adequate blood flow. The most common cause is infection with Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium that damages the mucosal lining and promotes inflammation. Another major cause is the chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, reducing mucosal protection. Other contributing factors include smoking, alcohol, stress, and genetic predisposition.

Causes

Helicobacter pylori infection

NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs)

Stress (severe illness, burns, trauma)

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (gastrinoma)

Smoking

Alcohol consumption

Excessive caffeine intake

Genetic predisposition

Hypersecretory states

Malignancy (gastric cancer can mimic ulcers)

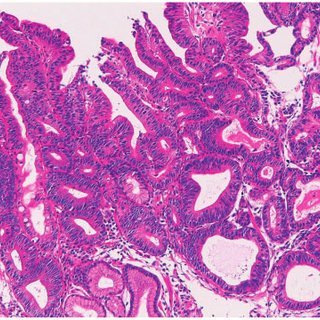

Pathophysiology

Peptic Ulcer results from an imbalance between aggressive factors and the protective mechanisms of the gastric or duodenal mucosa. Increased aggressive factors such as gastric acid and pepsin cause mucosal damage. Helicobacter pylori infection contributes by damaging the mucosa and increasing acid secretion. NSAIDs impair mucosal defenses by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, which reduces mucus and bicarbonate production. Smoking and alcohol further decrease mucosal blood flow and impair healing. At the same time, a reduction in protective factors like mucus secretion, bicarbonate, mucosal blood flow, epithelial regeneration, and prostaglandins leads to weakened mucosal defense. This imbalance ultimately results in mucosal injury and ulcer formation. In Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, excessive acid secretion caused by a gastrin-secreting tumor leads to multiple and difficult-to-treat ulcers.

Signs & Symptoms

Epigastric pain (burning or gnawing)

Pain related to meals:

Duodenal ulcer: pain relieved by eating, recurs 2–3 hours after meals

Gastric ulcer: pain worsens with eating

Dyspepsia (indigestion)

Nausea and vomiting

Bloating and early satiety

Weight loss (especially in gastric ulcers)

Hematemesis or melena (if bleeding occurs)

Signs of perforation (acute severe abdominal pain, rigidity)

Anemia symptoms (fatigue, pallor) if chronic bleeding

Types of Peptic Ulcer

| Feature | Gastric Ulcer | Duodenal Ulcer |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Stomach (usually antrum) | First part of duodenum |

| Pain relation to food | Worsens with eating | Relieved by eating |

| Age group | Older adults | Younger adults |

| Acid secretion | Normal or decreased | Increased |

| Malignancy risk | Higher risk (needs biopsy) | Rarely malignant |

| Weight changes | Weight loss | normal |

| NSAIDs association | Strong association | Less association |

| Common cause | H. pylori, NSAIDs | H. pylori |

| Bleeding risk | Moderate | Higher risk |

Risk Factors

Helicobacter pylori infection

Regular or prolonged use of NSAIDs (aspirin, ibuprofen, etc.)

Smoking tobacco

Excessive alcohol consumption

High stress levels (especially severe physical stress like trauma or surgery)

Older age (mucosal defenses weaken with age)

Family history of peptic ulcers

Certain medical conditions (e.g., Zollinger-Ellison syndrome)

Use of corticosteroids or anticoagulants (which can increase bleeding risk)

Poor diet or irregular eating habits (less directly, but may worsen symptoms)

Investigations & Lab Results

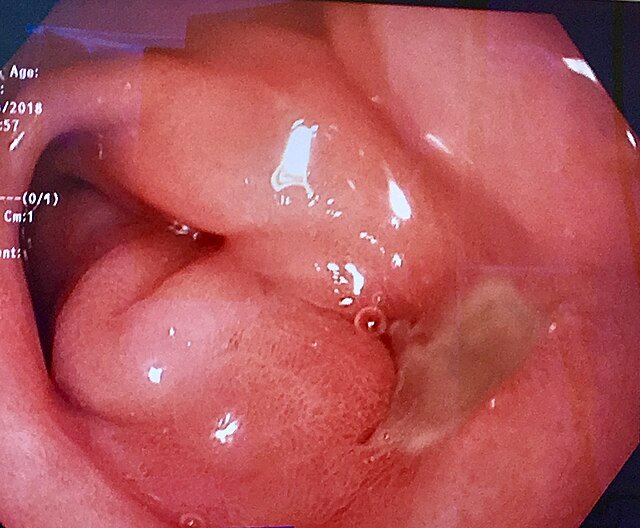

-Endoscopy (Gold Standard)

Direct visualization of ulcer

Location, size, depth assessment

Biopsy to rule out malignancy (especially in gastric ulcers)

Rapid urease test for H. pylori detection

-H. pylori Testing

Urea breath test (non-invasive, highly sensitive)

Stool antigen test (non-invasive, reliable)

Serology for H. pylori antibodies (less preferred, can’t differentiate past vs. current infection)

Biopsy with histology (via endoscopy)

-Blood Tests

Complete blood count (CBC) – may show anemia if bleeding

Iron studies – may show iron deficiency anemia

Liver and renal function tests – to rule out other causes or pre-endoscopy check

Serum gastrin levels – elevated in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

-Imaging (if perforation or obstruction suspected)

Abdominal X-ray – free air under diaphragm (perforation)

CT scan of abdomen – complications like perforation, penetration, or obstruction

Barium meal X-ray (less commonly used now) – shows ulcer crater or deformity

-Stool Occult Blood Test

Detects gastrointestinal bleeding (positive if ulcer is bleeding)

Complications

Bleeding (most common complication; can cause hematemesis or melena)

Perforation (sudden severe abdominal pain, peritonitis)

Penetration (ulcer extends into adjacent organs like pancreas)

Gastric outlet obstruction (due to edema or scarring)

Malignancy (especially in gastric ulcers)

Intractable pain

Fistula formation (rare)

Treatment

Eradication of H. pylori

Triple therapy: PPI + Clarithromycin + Amoxicillin/Metronidazole

Quadruple therapy (if resistance or failure): PPI + Bismuth + Metronidazole + Tetracycline

Acid Suppression

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) – mainstay (e.g., omeprazole, pantoprazole)

H2 receptor blockers – alternative (e.g., ranitidine, famotidine)

Stop NSAIDs

Discontinue NSAIDs if possible

Use PPIs if NSAIDs are necessary

Lifestyle Modifications

Smoking cessation

Avoid alcohol

Avoid caffeine and spicy foods

Stress management

Treatment of Complications

Bleeding: endoscopic hemostasis, PPI infusion, surgery if uncontrolled

Perforation: emergency surgery

Obstruction: endoscopic dilation or surgery

Penetration: manage surgically if severe

Surgery (rarely needed today)

For refractory ulcers, complications, or suspected malignancy