Filariasis

Content of This Page

1- Introduction

2- Causative Parasites

3- Pathophysiology

4- Epidemiology and Risk Factors

5- Clinical Features

6- Investigations

7- Treatment

8- Prognosis & Follow-up

Introduction

Filariasis is a parasitic disease caused by infection with filarial nematodes (roundworms), transmitted by mosquitoes. It is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions, especially parts of Asia, Africa, the Western Pacific, and the Americas. The most common form is lymphatic filariasis, which affects the lymphatic system, leading to chronic swelling (lymphoedema) and in severe cases, elephantiasis (massive enlargement of limbs or genitals).

Causative Parasites

Filariasis in humans is caused by:

Wuchereria bancrofti (most common; global distribution)

Brugia malayi (Southeast Asia)

Brugia timori (Indonesia)

These parasites are transmitted via mosquito vectors such as Culex, Anopheles, and Mansonia species.

Pathophysiology

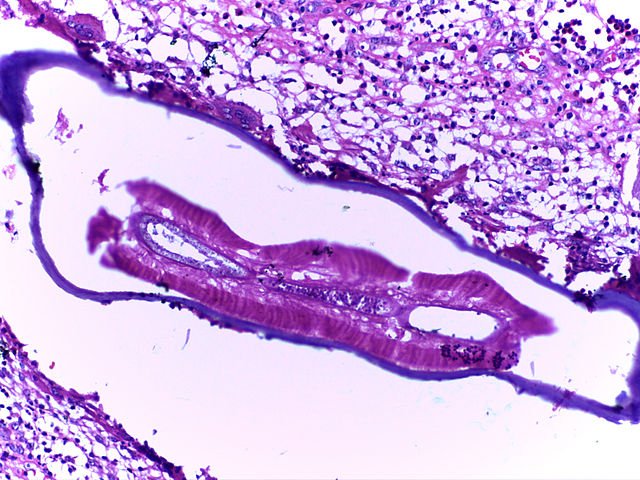

1. Entry and Development of Adult Worms

Infection begins when mosquitoes inject third-stage larvae into human skin during a blood meal.

These larvae migrate to the lymphatic vessels, where they mature into adult worms over 6 to 12 months.

Adult worms primarily reside in the lymphatic system, especially affecting vessels in the lower limbs, scrotum, breasts, and pelvic lymphatics.

2. Lymphatic Dilation and Obstruction

Adult worms occupy and dilate lymphatic vessels (lymphangiectasia).

Over time, this causes valve dysfunction and lymph stasis.

Mechanical obstruction is compounded by inflammation and fibrosis, which damage the vessel walls and reduce lymph drainage.

The death of adult worms releases additional antigens, intensifying the local immune response.

3. Role of Wolbachia

Wolbachia are intracellular bacteria that live symbiotically within filarial worms.

Upon worm death, these bacteria are released and activate pattern recognition receptors (like TLR-4) in host immune cells.

This leads to enhanced inflammation, which contributes to lymphatic damage, tissue remodeling, and scarring.

4. Host Immune Response

The initial immune response is Th1-dominant, involving macrophages and neutrophils.

Over time, there is a shift to a Th2-type response, dominated by eosinophils, IgE, and cytokines like IL-4, IL-5, IL-13.

Chronic immune activation causes:

Persistent lymphatic inflammation

Fibrosis of lymph nodes and vessels

Recurrent bacterial infections that further aggravate tissue damage

Pathophysiology of Tropical Pulmonary Eosinophilia (TPE)

This is an immunological complication caused by microfilariae trapped in the pulmonary microcirculation.

It leads to:

Marked eosinophilia

High serum IgE

Interstitial inflammation and fibrosis in the lungs

Clinically, this presents as nocturnal cough, wheezing, and breathlessness with restrictive pulmonary function defects.

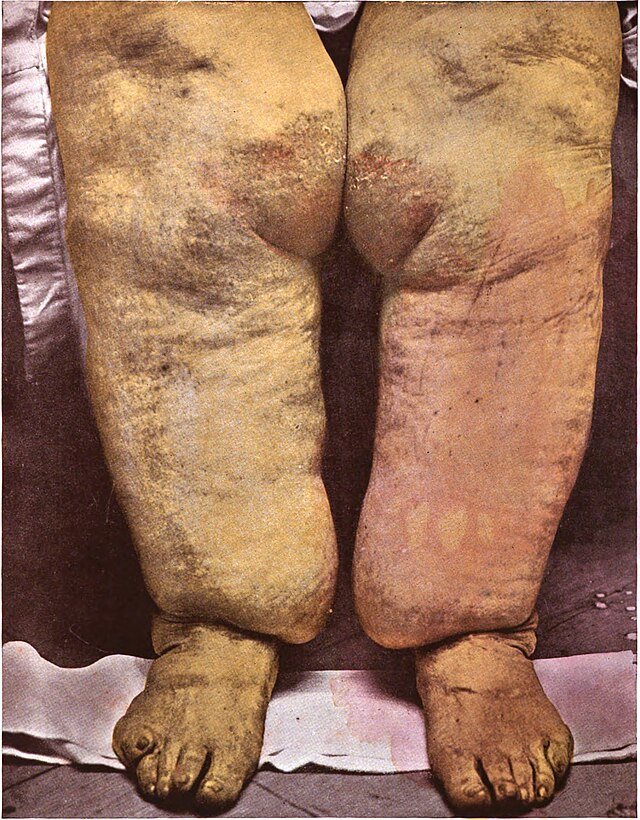

End Result: Elephantiasis

Chronic lymphatic obstruction leads to lymphoedema, which progresses to:

Skin thickening

Fibrosis

Hyperkeratosis

Massive swelling of limbs or genitalia

Commonly affected areas include the legs, scrotum (hydrocele), vulva, and breasts.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Epidemiology

Lymphatic filariasis is a major public health problem in many tropical and subtropical regions. It is one of the leading causes of long-term disability worldwide and is classified by the WHO as a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD).

Global burden: Over 120 million people are infected across more than 80 countries.

At-risk population: Over 850 million people are at risk of infection in endemic areas.

Most common species:

Wuchereria bancrofti (accounts for about 90% of infections)

Brugia malayi and Brugia timori (more geographically limited)

Endemic regions:

Sub-Saharan Africa

South and Southeast Asia (especially India, Indonesia, Philippines)

Western Pacific

Parts of Central and South America

Transmission vector: Spread by mosquito species such as Culex, Anopheles, and Mansonia, which breed in stagnant or slow-flowing water.

Risk Factors

Geographic Location

Living in or frequent travel to endemic tropical or subtropical areas.

Risk is higher in rural and peri-urban regions with poor sanitation.

Mosquito Exposure

Areas with high mosquito density, especially night-biting species.

Living near open water bodies, rice fields, or swamps increases vector contact.

Housing and Environmental Conditions

Poor housing structures (e.g. no window screens or nets).

Lack of access to vector control measures.

Occupation

Outdoor workers (e.g. farmers, construction workers) are at increased risk due to more frequent mosquito exposure.

Poor Public Health Infrastructure

Areas with inadequate mosquito control programs and limited mass drug administration (MDA) coverage have persistent transmission.

Duration of Exposure

Long-term residence in an endemic area increases cumulative risk of infection.

Immunological Susceptibility

Not all infected individuals develop clinical disease; host immune responses and co-infections may influence disease progression.

Clinical Features

1. Asymptomatic Phase

Most individuals show no symptoms despite microfilariae in blood

Still contribute to disease transmission

2. Acute Manifestations

Filarial lymphangitis: Fever, pain, redness along lymphatics (e.g. legs, spermatic cord)

Epididymo-orchitis: Painful scrotal swelling, especially in young males

3. Chronic Manifestations

Lymphoedema: Persistent swelling of limbs, breast, or genitals

Elephantiasis: End-stage disease with gross enlargement, thickened skin, fibrosis

Hydrocele: Fluid in scrotal sac, often large and disfiguring

Chyluria: Milky urine due to lymph leakage into urinary tract

4. Tropical Pulmonary Eosinophilia (TPE)

Immune response to trapped microfilariae in lungs

Features: Nocturnal cough, wheeze, dyspnoea, eosinophilia, elevated IgE

Investigations

1. Night Blood Film

Detects microfilariae in peripheral blood

Sample must be taken at night (10 pm–2 am)

2. Antigen Detection (Card Test)

Identifies W. bancrofti antigen

Can be done at any time of day

Useful in chronic or occult infections

3. Serology

ELISA/IFA detect filarial antibodies

High sensitivity but not species-specific

4. PCR

Detects filarial DNA

Highly sensitive and species-specific

Useful when microfilariae are absent

5. Imaging

Scrotal ultrasound: May show adult worms

Lymphoscintigraphy: Evaluates lymphatic drainage

6. Tropical Pulmonary Eosinophilia

Eosinophilia (>3000/μL), ↑ IgE

Chest X-ray: Miliary infiltrates

PFTs: Restrictive pattern

7. Urine Tests

Milky urine → chyluria

Urine microscopy: Shows lymphocytes or chyle

Treatment

1. Antifilarial Drug Therapy

a. Diethylcarbamazine (DEC)

Standard drug for lymphatic filariasis

Dose: 2 mg/kg three times daily for 12 days or single dose of 6 mg/kg

Effective against both microfilariae and adult worms

Side effects:

Often due to the immune reaction to dying parasites

Include fever, malaise, arthralgia

Managed with antihistamines or corticosteroids

2. Combination Therapy (for enhanced efficacy and global eradication efforts)

DEC + Albendazole

In some endemic regions: Albendazole + Ivermectin ± DEC

Rationale: Broader activity against microfilariae and intestinal helminths, better transmission control

3. Treatment of Tropical Pulmonary Eosinophilia (TPE)

DEC for 14–21 days is highly effective

Important: Rule out Strongyloides infection before giving steroids

4. Wolbachia-Targeted Therapy

Doxycycline 200 mg daily for 4–8 weeks

Kills Wolbachia, the symbiotic bacteria essential for worm fertility and survival

Leads to sterilization and gradual death of adult worms

Helps reduce disease progression and transmission

5. Supportive and Symptomatic Management

a. For Lymphoedema and Elephantiasis

Limb hygiene and elevation

Exercise and compression bandaging

Skin care to prevent bacterial superinfection

Surgical options (e.g. debulking) may help in advanced cases but are not curative

b. For Hydrocele

Surgical correction (hydrocelectomy) for symptomatic relief

c. For Chyluria

Low-fat diet, supportive measures

In severe cases: surgical intervention or sclerotherapy

6. Mass Drug Administration (MDA)

Public health strategy in endemic regions:

Annual single-dose DEC + Albendazole

Aims to reduce microfilarial load in the community and interrupt transmission

Prognosis & Follow-up

Prognosis

Good if diagnosed and treated early (e.g. microfilaraemia, acute lymphangitis).

Chronic complications (lymphoedema, elephantiasis, hydrocele) may persist even after parasite clearance due to irreversible lymphatic damage.

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia (TPE) responds well to DEC; untreated cases risk lung fibrosis.

Follow-up

Monitor symptoms and parasite clearance (e.g. antigen test, PCR, eosinophils).

Long-term care for chronic cases includes:

Limb circumference checks (lymphoedema)

Urine monitoring (chyluria)

Ultrasound for persistent hydrocele

Educate patients on:

Daily limb hygiene and elevation

Infection prevention

Adherence to treatment and participation in mass drug administration (MDA)