Grand Mal Epilepsy

content of this page

1- Introduction

2- Pathophysiology

3- Symptoms

4- Treatment

Introduction

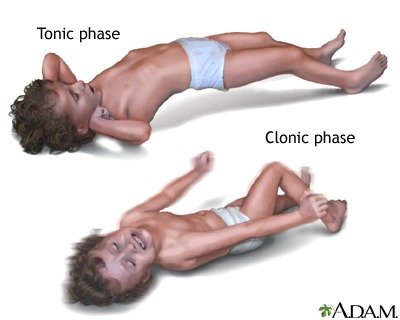

Grand Mal epilepsy, also known as generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) or convulsive epilepsy, is a type of epileptic seizure characterized by sudden and intense muscle contractions (tonic phase) followed by rhythmic muscle jerking (clonic phase). It is one of the most well-known and recognizable types of seizures and can be alarming to witness.

Pathophysiology

Grand Mal epilepsy, also known as generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS), involves complex neurological mechanisms that underlie the characteristic tonic and clonic phases observed during a seizure. Understanding the pathophysiology of Grand Mal epilepsy helps elucidate how abnormal electrical activity in the brain leads to these dramatic clinical manifestations. Here’s an overview of the key aspects of the pathophysiology:

1. Neuronal Hyperexcitability and Synchronization:

- Neuronal Networks: In epilepsy, including Grand Mal seizures, there is an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission within neuronal networks in the brain.

- Hyperexcitability: Certain neurons become more excitable, leading to an increased likelihood of synchronous firing and abnormal electrical discharges.

2. Initiation of Seizure Activity:

- Focal Onset: Grand Mal seizures often arise from widespread, synchronous activation of neurons throughout both hemispheres of the brain.

- Thalamocortical Loop: Abnormal firing patterns begin in the thalamus and spread to involve the cerebral cortex and subcortical structures, disrupting normal brain function.

3. Tonic Phase:

- Tonic Contraction: The seizure begins with a tonic phase characterized by sudden, sustained muscle contraction due to simultaneous activation of motor neurons.

- Loss of Inhibitory Control: During this phase, inhibitory neurotransmitters such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) fail to adequately suppress excitatory signals, resulting in prolonged muscle rigidity.

4. Clonic Phase:

- Rhythmic Jerking: The tonic phase transitions into the clonic phase, marked by rhythmic, alternating contractions and relaxations of muscles.

- Disrupted Cortical Function: The clonic phase reflects the ongoing abnormal electrical activity affecting motor areas of the brain, leading to repetitive muscle movements.

5. Postictal Phase:

- Recovery Period: Following the clonic phase, there is a postictal phase characterized by neuronal exhaustion and temporary suppression of brain activity.

- Neurotransmitter Imbalance: Changes in neurotransmitter levels, including depletion of excitatory neurotransmitters and accumulation of inhibitory neurotransmitters, contribute to the cessation of seizure activity.

6. Underlying Causes and Triggers:

- Structural Abnormalities: Brain injuries, tumors, stroke, or developmental abnormalities can predispose individuals to epilepsy and Grand Mal seizures.

- Genetic Factors: Inherited mutations affecting ion channels or neurotransmitter receptors can increase susceptibility to abnormal neuronal excitability.

- Environmental Triggers: Factors such as stress, sleep deprivation, flashing lights (photosensitivity), and certain medications can provoke seizures in susceptible individuals.

7. Role of Ion Channels and Neurotransmitters:

- Ion Channel Dysfunction: Mutations or alterations in ion channels (e.g., sodium, potassium, calcium channels) disrupt normal neuronal membrane potentials, leading to spontaneous depolarization and hyperexcitability.

- GABAergic System: Deficiencies in GABAergic inhibition, either due to impaired synthesis or increased degradation of GABA, contribute to the dysregulation of neuronal activity seen in epilepsy.

8. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches:

- Electroencephalography (EEG): Recording electrical activity from the brain helps identify abnormal patterns characteristic of epilepsy, guiding diagnosis and treatment.

- Antiepileptic Drugs (AEDs): Medications aim to stabilize neuronal membranes, enhance inhibitory neurotransmission (e.g., GABAergic agents), or modulate ion channel activity to reduce seizure frequency and severity.

- Surgical Interventions: For individuals with medically refractory Grand Mal epilepsy, surgical removal of seizure foci or placement of devices such as vagus nerve stimulators may be considered to prevent seizures.

Symptoms

Grand Mal epilepsy, also known as generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS), manifests with distinct symptoms that involve both motor and non-motor aspects. These seizures are characterized by their dramatic nature, involving sudden loss of consciousness and intense muscle contractions. Here are the key symptoms typically observed during a Grand Mal seizure:

Pre-Seizure Phase (Prodrome):

- Aura: Some individuals experience a warning sensation or aura before the seizure begins. Auras can vary widely and may include visual disturbances, strange smells or tastes, feelings of fear or déjà vu, or tingling sensations.

Tonic Phase:

- Loss of Consciousness: The seizure usually begins abruptly with a loss of consciousness.

- Muscle Stiffening (Tonic Phase): During this phase, all the muscles in the body suddenly contract, causing the person to become rigid. This can lead to:

- Arched Back: The person may arch their back due to intense muscle contraction.

- Jaw Clenching: Jaw muscles can become tightly clenched.

- Involuntary Cry or Shout: A sudden, involuntary cry or shout may occur due to the forceful expiration of air from the lungs.

Clonic Phase:

- Rhythmic Jerking Movements: Following the tonic phase, the muscles begin to jerk rhythmically:

- Convulsions: These rhythmic movements typically involve both sides of the body symmetrically, including the arms, legs, and sometimes the face.

- Bowel or Bladder Incontinence: Loss of control over bowel or bladder function may occur due to the intense muscle contractions.

Postictal Phase:

- Recovery Period: After the clonic movements cease, the person enters the postictal phase, characterized by gradual recovery and reorientation.

- Confusion and Disorientation: The individual may be confused, disoriented, and have no memory of the seizure or events leading up to it.

- Extreme Fatigue: Seizures are physically and mentally exhausting, and the person may feel extremely tired or drowsy.

- Headache: Some individuals experience headaches or muscle aches after the seizure.

Additional Symptoms:

- Injuries: Due to the sudden loss of consciousness and convulsive movements, injuries such as tongue biting, injuries from falls, or muscle strains can occur.

- Cardiovascular Changes: There may be changes in heart rate or blood pressure during the seizure.

Behavioral and Emotional Aspects:

- Emotional Impact: Seizures can be emotionally distressing for both the person experiencing them and those witnessing them.

- Fear or Anxiety: Anxiety about when the next seizure might occur can affect daily life and emotional well-being.

Duration:

- The entire seizure episode, including the tonic and clonic phases, typically lasts from a few seconds to a few minutes. However, the recovery period (postictal phase) can vary in length and may last minutes to hours.

Treatment

The treatment of Grand Mal epilepsy, also known as generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS), typically involves a multifaceted approach aimed at controlling seizures, ensuring safety during episodes, and improving overall quality of life. Here are the key components of treatment:

1. Antiepileptic Medications (AEDs):

First-Line Therapy: The cornerstone of treatment for Grand Mal epilepsy is the use of antiepileptic medications to prevent seizures.

Medication Selection: The choice of AED depends on various factors including seizure type, individual response, potential side effects, and patient preferences.

Examples of AEDs:

- Sodium Valproate (Valproic Acid): Effective for generalized and focal seizures, including GTCS.

- Carbamazepine: Often prescribed for focal seizures, it can also be effective in controlling generalized seizures.

- Lamotrigine: Used in generalized seizures and can be particularly useful if there is a concern about cognitive side effects with other medications.

- Levetiracetam: Effective across different seizure types, including GTCS, and is well-tolerated with fewer drug interactions.

Drug Dosage and Monitoring: AEDs are prescribed at doses adjusted to achieve seizure control while minimizing side effects. Regular monitoring of drug levels and potential interactions with other medications is essential.

2. Lifestyle Modifications:

- Sleep and Stress Management: Ensuring adequate sleep and managing stress can help reduce seizure frequency.

- Avoiding Triggers: Identifying and avoiding triggers such as alcohol, flashing lights (photosensitivity), and specific medications that can precipitate seizures.

- Regular Exercise and Nutrition: Maintaining a healthy lifestyle with regular physical activity and a balanced diet can contribute to overall well-being and seizure management.

3. Seizure Safety Precautions:

- Education and Support: Providing education to patients, families, and caregivers about recognizing seizure triggers and managing seizures safely.

- Safety Measures: Ensuring a safe environment to prevent injuries during seizures, such as padding sharp corners, using helmets if needed, and avoiding activities like swimming alone.

4. Surgical Options:

- Epilepsy Surgery: For individuals with medically refractory seizures (seizures not controlled by medications), surgical removal of the seizure focus (e.g., temporal lobe) may be considered.

- Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS): Involves implanting a device that sends electrical impulses to the vagus nerve, which can help reduce seizure frequency.

5. Management of Acute Seizures:

- Emergency Medications: Prescription of rescue medications such as diazepam or lorazepam to be administered during prolonged seizures or clusters of seizures (status epilepticus).

- Hospitalization: Occasionally, hospitalization may be required for intensive monitoring and management of severe or prolonged seizures.

6. Monitoring and Follow-Up:

- Regular Follow-Up: Scheduled visits with healthcare providers to monitor seizure control, adjust medication dosages as needed, and address any concerns or side effects.

- EEG Monitoring: Periodic electroencephalogram (EEG) to assess brain activity and seizure patterns, guiding treatment decisions.

7. Psychosocial Support:

- Counseling and Support Groups: Providing psychological support and resources to cope with the emotional and social challenges associated with epilepsy.

- Educational and Vocational Assistance: Helping individuals with epilepsy to navigate educational and employment settings, ensuring accommodations and support are in place.

8. Comprehensive Care Team:

- Neurologist and Epileptologist: Specialized healthcare providers who oversee diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of epilepsy.

- Multidisciplinary Approach: Collaboration with neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists, nurses, and other healthcare professionals to provide holistic care.