Renal Cell Carcinoma

Content of This Page

1- Definition & Types

2- Causes (Aetiology)

3- Pathophysiology

4- Clinical Features & Examination

5- Investigations

6- Management

7- Complications

8- Core Concepts

Definition & Types

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common type of primary kidney cancer, accounting for approximately 90% of all kidney malignancies. It arises from the epithelial cells of the renal tubules, most commonly from the proximal convoluted tubule.

Subtypes of RCC include:

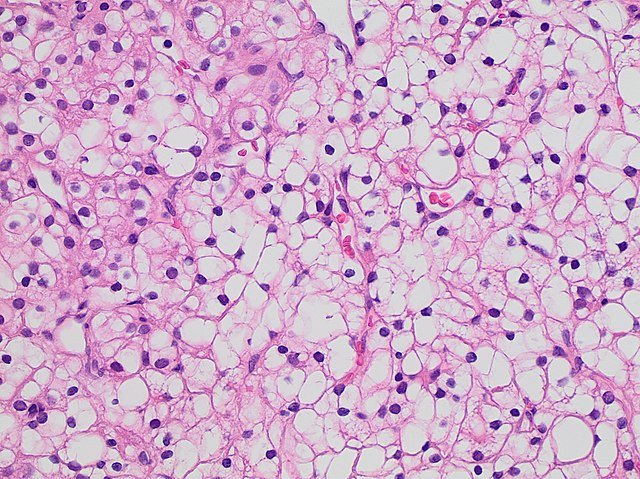

Clear cell RCC (75%): The most common subtype; often linked to VHL gene mutations.

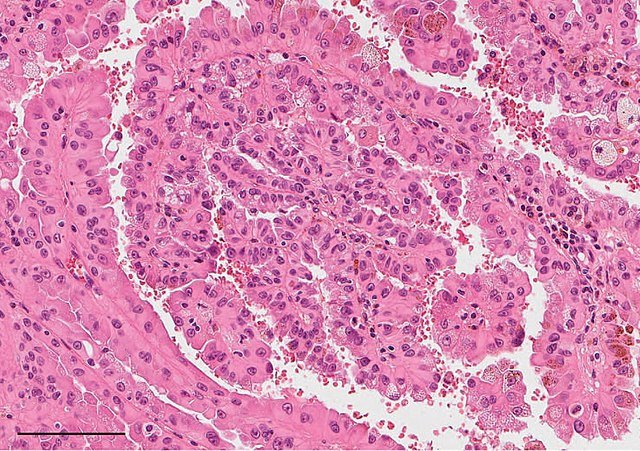

Papillary RCC (15%): Can be further subdivided into type 1 and type 2; sometimes associated with MET gene mutations.

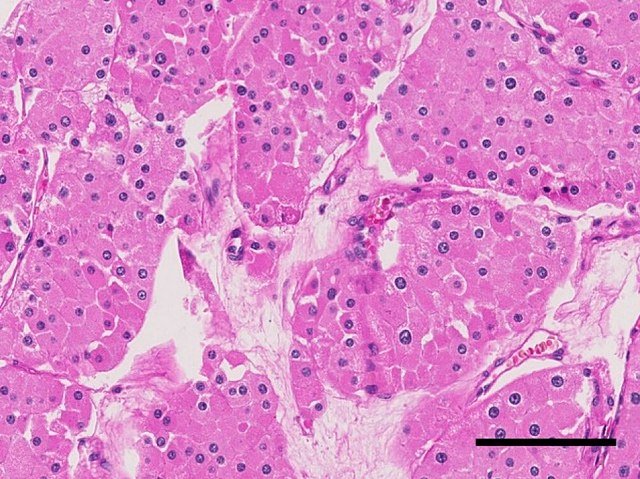

Chromophobe RCC (5%): Arises from intercalated cells of the collecting duct.

Collecting duct carcinoma and medullary carcinoma: Rare and aggressive forms.

These subtypes differ in their genetic mutations, histological features, and clinical behaviour.

Causes (Aetiology)

Several risk factors have been identified for RCC:

Environmental and lifestyle-related:

Smoking: Strongest known modifiable risk factor.

Obesity: Increased risk due to hormonal and inflammatory mechanisms.

Hypertension: Possibly through chronic renal hypoxia or metabolic changes.

Medical conditions:

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and acquired cystic kidney disease, especially in long-term dialysis patients.

Renal transplantation: Increased risk of RCC in the native kidneys of transplant recipients.

Genetic predisposition:

Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) syndrome: An autosomal dominant condition associated with clear cell RCC.

Hereditary papillary RCC: Linked to MET gene mutations.

Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome: A rare genetic syndrome associated with chromophobe RCC and other tumour types.

Occupational exposures:

Prolonged exposure to certain chemicals such as cadmium, asbestos, and petroleum products may increase risk.

Pathophysiology

RCC typically originates from renal tubular epithelial cells, most often from the proximal tubule.

In clear cell RCC, the most common form, the VHL gene is frequently inactivated. This leads to:

Upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs).

Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), promoting angiogenesis and tumour growth.

The tumour tends to be hypervascular and may demonstrate:

Invasion into adjacent structures, especially the renal vein and inferior vena cava (IVC).

Early haematogenous spread to the lungs, bones, liver, and brain.

Clinical Features & Examination

Classical Triad (occurs in <10% of cases):

Haematuria – visible or microscopic blood in urine.

Loin pain – due to local invasion or mass effect.

Palpable abdominal mass – more common in advanced disease.

More common presentations:

Incidental finding: Increasingly detected during imaging for unrelated reasons.

Paraneoplastic syndromes, including:

Polycythaemia: Due to ectopic erythropoietin production.

Hypercalcaemia: Often via secretion of parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP).

Hypertension: Related to renin secretion.

Hepatic dysfunction (Stauffer’s syndrome): Non-metastatic hepatic abnormalities.

Left-sided varicocele: Due to obstruction of the left renal vein.

Physical Examination:

May reveal an abdominal mass.

Signs of paraneoplastic syndromes or metastatic disease (e.g. bone tenderness, respiratory symptoms).

Features of chronic kidney disease if bilateral or contralateral renal function is impaired.

Investigations

Imaging:

Ultrasound: Useful initial modality; may show a solid mass.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen: Preferred for diagnosis and staging. Can assess tumour size, local invasion, and vascular involvement.

MRI: Used when CT contrast is contraindicated or to assess venous extension into the IVC.

Chest imaging (X-ray or CT): To look for pulmonary metastases.

Laboratory tests:

Urinalysis: May show haematuria.

Urine cytology: To exclude urothelial carcinoma.

Blood tests:

Full blood count: May reveal polycythaemia or anaemia.

Serum calcium: May be elevated.

Renal function: Important for staging and treatment planning.

Liver function tests: For possible Stauffer’s syndrome.

Biopsy is rarely performed unless the diagnosis is uncertain, or in selected cases such as unresectable or metastatic disease.

Management

Localised RCC:

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment.

Radical nephrectomy: Complete removal of the kidney, surrounding fat, and sometimes adrenal gland.

Partial nephrectomy (nephron-sparing surgery): Preferred for small peripheral tumours, especially in solitary kidneys or CKD.

Advanced or metastatic RCC:

Systemic therapy is the main approach, as RCC is resistant to traditional chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs): e.g. sunitinib, pazopanib.

mTOR inhibitors: e.g. everolimus.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors: e.g. nivolumab, pembrolizumab.

Cytoreductive nephrectomy: May be considered in selected patients with metastatic disease to reduce tumour burden.

Radiotherapy: Used for palliation of symptoms from metastases (e.g. bone or brain lesions).

Complications

Metastatic disease: Commonly affects lungs, bones, liver, brain.

Renal vein or IVC invasion: Can lead to venous obstruction and embolic complications.

Paraneoplastic syndromes: May cause systemic effects and metabolic derangements.

Postoperative complications: Including bleeding, infection, and renal insufficiency if the contralateral kidney is impaired.

Progression to end-stage renal disease in bilateral or solitary kidney involvement.

Core Concepts

RCC is often asymptomatic in early stages and frequently detected incidentally during imaging.

Paraneoplastic features, such as hypercalcaemia or polycythaemia, may be the first clinical clue.

Histological subtype and staging determine prognosis and treatment strategy.

Surgical resection remains the cornerstone for localised disease, while targeted and immune therapies have transformed management of advanced RCC.

Careful imaging evaluation is crucial, especially for assessing venous involvement and metastases.