Absence Seizures

Content of This Page

1- Introduction

2- Causes

3- Symptoms

4- Tyoes of Absence Seizures

5- Investigations & Lab Results

6- Complications

7- Treatment

8- Prognosis

Introduction

Absence seizures are a type of generalized non-motor seizure characterized by brief, sudden lapses in consciousness. Most commonly seen in children aged 4 to 10 years, these seizures often appear as sudden episodes where the child “blanks out” or “stares into space” for a few seconds, typically without any warning and without post-ictal confusion.

They are associated with generalized epilepsy syndromes, most notably Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE). Unlike convulsive seizures, absence seizures are non-convulsive and can go unnoticed for long periods, often being mistaken for inattentiveness or daydreaming in school settings.

These seizures are often triggered by hyperventilation, and the hallmark diagnostic feature on EEG is a 3 Hz spike-and-wave discharge. Though typically benign and self-limiting in childhood, timely diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent cognitive and behavioral impairments.

Causes

1. Idiopathic (Primary) Causes

These are the most common, especially in children:

Genetic predisposition

(Often a family history of epilepsy or seizures)Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE) – typically between ages 4–10

Juvenile Absence Epilepsy (JAE) – later onset in adolescence

Channelopathies – mutations in ion channels (e.g., T-type calcium channels) involved in neuronal excitability

2. Secondary (Symptomatic) Causes

Less common and often associated with underlying brain abnormalities or systemic conditions:

Brain malformations (e.g., cortical dysplasia)

Metabolic disorders (e.g., hypoglycemia, mitochondrial diseases)

Neurodegenerative diseases

Head trauma (rarely)

Infections affecting the CNS (e.g., encephalitis)

Toxic exposures or withdrawal from certain drugs

3. Triggers (Not true causes, but can provoke seizures)

Hyperventilation

Flashing lights (photosensitivity)

Stress or emotional disturbances

Lack of sleep

Skipping medications

Symptoms

-Core Symptoms

Sudden, brief lapse in awareness (usually 5–20 seconds)

Staring blankly or “zoning out”

Unresponsive during the episode

Abrupt onset and termination – no warning and no post-ictal confusion

No memory of the event afterward

-Associated Features (in some cases)

Automatisms (involuntary repetitive movements)

Lip smacking

Eye blinking or fluttering

Chewing motions

Finger rubbing or hand movements

Mild facial twitching

Mild reduction in muscle tone (but not enough to cause collapse)

Speech interruption if the patient is talking

-Frequency and Duration

Can occur dozens to hundreds of times per day

Each episode usually lasts 5–20 seconds

-Important Notes

The child usually resumes activity immediately after the seizure

No aura before the seizure

No confusion or fatigue afterward

Often first noticed by teachers or parents due to poor attention in class

Types of Absence Seizures

1. Typical Absence Seizures

Most common form, especially in children

Sudden onset and sudden end

Lasts about 5 to 20 seconds

Characterized by:

Brief loss of awareness or staring spells

Minimal or no motor symptoms (may have subtle automatisms like eye blinking or lip-smacking)

EEG shows generalized 3 Hz spike-and-wave discharges

Often triggered by hyperventilation

Usually part of Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE)

Generally respond well to treatment and have a good prognosis

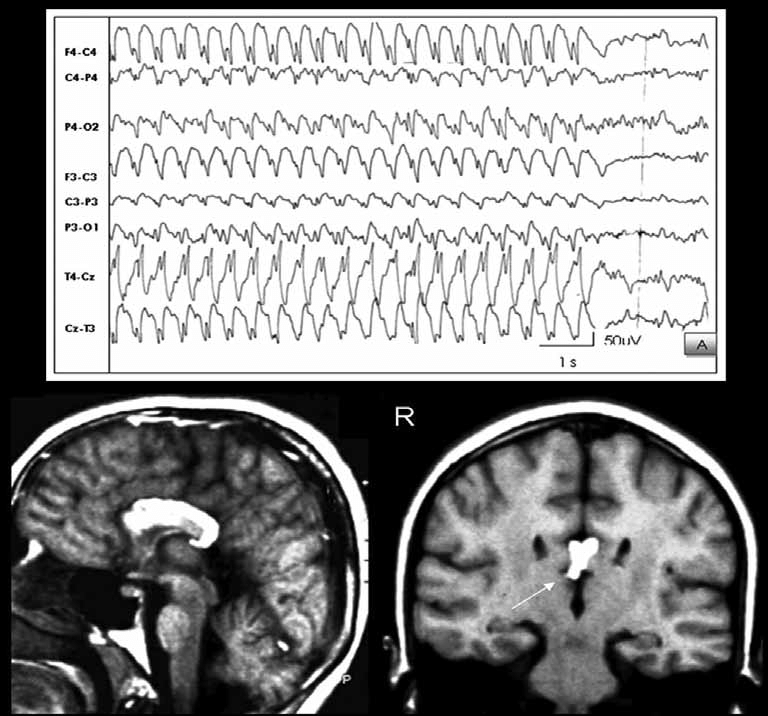

2. Atypical Absence Seizures

Less common; usually seen in patients with developmental delay or other neurological abnormalities

Gradual onset and offset, lasting longer than typical absence seizures (up to several seconds or minutes)

More pronounced motor symptoms such as:

Slower impairment of consciousness

Changes in muscle tone (e.g., mild jerking or tonic posturing)

EEG shows slower (<2.5 Hz) and irregular spike-and-wave complexes

Often associated with syndromes such as Lennox-Gastaut syndrome

More resistant to treatment and poorer prognosis

Investigations & Lab Results

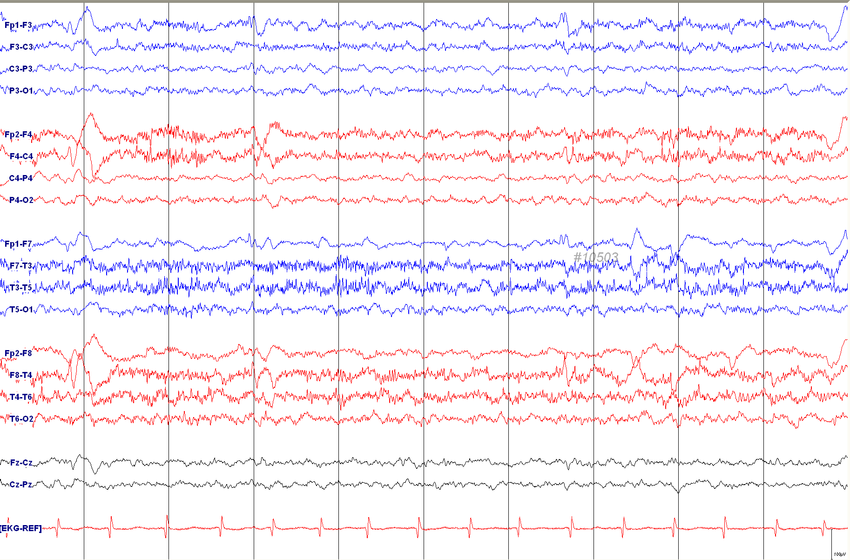

1. Electroencephalogram (EEG) – Most important test

Classic finding: generalized 3 Hz spike-and-wave discharges

These discharges are symmetrical and synchronous across both hemispheres

May be provoked by hyperventilation during EEG

Atypical absence seizures may show slower (<2.5 Hz) spike-and-wave activity

EEG is both diagnostic and specific for absence seizures

2. Hyperventilation Provocation Test

Performed during EEG to induce seizure activity

Hyperventilation for 3–5 minutes can provoke an absence seizure in susceptible individuals

Helps confirm the diagnosis in unclear cases

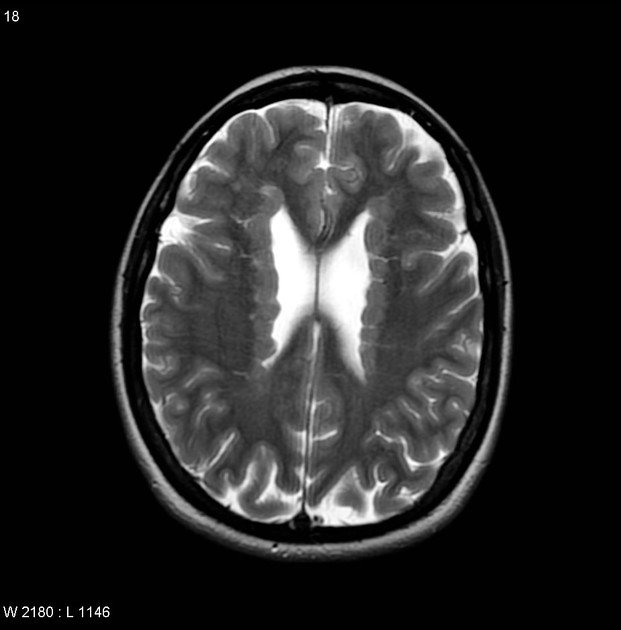

3. Neuroimaging (MRI or CT Brain)

Usually normal in typical absence seizures

Indicated only if:

Atypical features are present

Focal neurological signs or developmental delays exist

Seizures are refractory to treatment

4. Routine Blood Tests

Not diagnostic, but may be done to rule out secondary causes:

Glucose (to exclude hypoglycemia)

Electrolytes (to exclude metabolic causes)

Calcium and magnesium (if metabolic seizures are suspected)

5. Genetic Testing (rarely done)

May be considered in cases with a family history or suspected genetic epilepsy syndrome

Complications

1. Academic and Behavioral Issues

Frequent seizures (dozens to hundreds daily) can cause:

Poor concentration

Reduced academic performance

Difficulty in learning and memory

Misdiagnosis as ADHD or behavioral disorders

2. Social and Emotional Effects

Embarrassment or social isolation

Poor self-esteem, especially in older children or teens

Anxiety about having seizures in public or school

3. Safety Risks

Injury from unawareness during activities (e.g., crossing streets, swimming)

Interference with driving in older adolescents or adults

4. Progression to Other Seizure Types

Some patients may later develop:

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME)

Atypical absence seizures (more resistant to treatment)

5. Treatment Side Effects

Cognitive slowing, weight changes, or GI upset from medications like:

Valproic acid

Ethosuximide

Lamotrigine

6. Refractory Seizures (Rare)

In some cases (especially atypical absence seizures), seizures may be:

Resistant to treatment

Associated with neurodevelopmental syndromes like Lennox-Gastaut

7. Psychosocial Impact on Family

Emotional stress on caregivers

Difficulty managing school and daily life for the child

Treatment

1. First-Line Medications

–Ethosuximide

Drug of choice for typical absence seizures

Especially in Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE)

Few cognitive side effects

Not effective for other types of generalized seizures

Side effects: GI upset, drowsiness, headache

-Valproic Acid (Valproate)

Used when:

Patient has absence + generalized tonic-clonic seizures

Ethosuximide is not effective or not tolerated

Broad-spectrum antiepileptic

Side effects: weight gain, tremor, liver toxicity, teratogenicity (avoid in females of childbearing age unless necessary)

-Lamotrigine

Alternative if ethosuximide and valproate are not suitable

Fewer side effects but less effective

Side effects: rash (including rare SJS), dizziness

2. Other Treatment Options (in refractory or atypical cases)

Clobazam or Topiramate (less commonly used)

Ketogenic diet (in medically refractory epilepsy)

Surgical evaluation if seizures are resistant and another pathology is suspected (rare for pure absence seizures)

3. Supportive Management

Patient and family education

Avoid triggers: sleep deprivation, hyperventilation, stress, flashing lights

School support: address attention, memory, and performance issues

Regular follow-up and EEG monitoring

Prognosis

The prognosis of absence seizures depends on whether the seizures are typical or atypical, as well as the presence of other neurological or developmental conditions.

-Typical Absence Seizures

Generally favorable prognosis

Commonly associated with Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE)

Seizures often begin between ages 4 and 10

65–80% of children become seizure-free during adolescence

Normal cognitive development in most cases if well treated

Low risk of developing other seizure types

-Atypical Absence Seizures

Seen in more complex epilepsy syndromes like Lennox-Gastaut syndrome

Poorer prognosis

Often associated with:

Developmental delays

Cognitive impairment

Other seizure types (e.g., atonic, tonic, myoclonic)

More likely to be refractory to treatment

-Factors Indicating Good Prognosis

Early diagnosis and treatment

Good response to first-line anti-seizure medications

No other seizure types

Normal neurological development

Normal EEG background activity between seizures

-Factors Indicating Poor Prognosis

Atypical EEG patterns (e.g., slow spike-and-wave)

Coexisting seizure types

Developmental or intellectual impairment

Resistance to multiple anti-epileptic drugs