Ludwig’s Angina

content of this page

1- Introduction

2- Anatomical Overview

3- Causes

4- Treatment

Introduction

Ludwig’s angina is a severe, potentially life-threatening form of cellulitis that affects the submandibular and sublingual spaces of the head and neck. Named after the German physician Wilhelm Friedrich von Ludwig who first described it in 1836, Ludwig’s angina typically arises from a bacterial infection, most commonly by oral flora such as Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species.

Anatomical Overview

Submandibular Space:

- Located beneath the mandible (jawbone), the submandibular space is a potential space filled with loose connective tissue, fat, lymphatics, and glands.

- It contains important structures such as the submandibular gland, lymph nodes, and neurovascular bundles.

- In Ludwig’s angina, infection from dental or oral sources can rapidly spread within this space due to its anatomical continuity and lack of natural barriers, leading to bilateral swelling and inflammation.

Sublingual Space:

- Situated beneath the tongue, the sublingual space communicates with the submandibular space and extends posteriorly towards the floor of the mouth.

- It contains the sublingual gland, ducts, and vessels, surrounded by loose connective tissue.

- Infection can extend from the submandibular space into the sublingual space, contributing to the characteristic swelling and potential airway compromise seen in Ludwig’s angina.

Potential Complications:

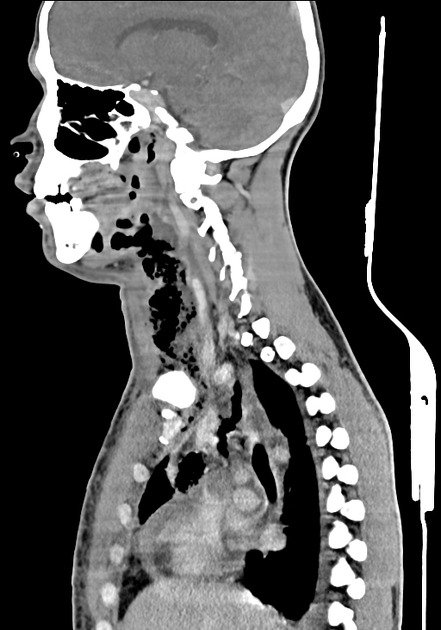

- Airway Compromise: Due to the rapid and extensive swelling in the submandibular and sublingual spaces, patients with Ludwig’s angina are at risk of upper airway obstruction. This is a critical concern that requires immediate recognition and intervention to maintain a patent airway.

- Spread to Deep Neck Spaces: Untreated or inadequately managed Ludwig’s angina can lead to further spread of infection to other deep neck spaces, such as the parapharyngeal space or retropharyngeal space. This can result in serious complications like mediastinitis, sepsis, and carotid artery erosion.

- Sepsis: The infection can lead to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and sepsis, necessitating aggressive antibiotic therapy and supportive care.

Clinical Presentation:

- Patients typically present with rapidly progressive bilateral neck and facial swelling, pain, fever, and difficulty swallowing (dysphagia).

- Trismus (inability to open the mouth fully) may also be present due to swelling and pain.

- In severe cases, patients may exhibit signs of respiratory distress due to upper airway compromise.

Diagnostic Evaluation:

- Diagnosis is primarily clinical based on history, physical examination, and imaging studies (such as CT scan) to assess the extent of the infection and rule out complications.

- Laboratory investigations may reveal leukocytosis (elevated white blood cell count) and inflammatory markers.

Causes

Dental Infections:

- Tooth decay (dental caries), periodontal disease (gum disease), or dental procedures that breach oral mucosa can introduce bacteria into the surrounding tissues.

- Infection can spread from infected teeth or gums into the adjacent soft tissues of the mouth and throat.

Odontogenic Infections:

- Infections arising from the teeth or their supporting structures (periodontium) are a primary source of pathogens causing Ludwig’s angina.

- Pulpal necrosis (death of dental pulp tissue) or periapical abscesses can lead to the spread of infection into the submandibular and sublingual spaces.

Trauma or Injury:

- Trauma to the mouth or jaw, such as lacerations, fractures, or penetrating injuries, can provide a pathway for bacteria to enter and cause infection.

- Invasive dental procedures, especially in individuals with compromised immune systems or poor oral hygiene, increase the risk of infection.

Oral Procedures:

- Invasive dental procedures, such as tooth extraction, root canal treatment, or dental implant placement, can potentially introduce bacteria into deeper tissues if proper sterile techniques are not followed.

Upper Respiratory Infections:

- In some cases, respiratory infections caused by bacteria can spread downward into the neck spaces, leading to cellulitis and inflammation characteristic of Ludwig’s angina.

- This route is less common compared to dental sources but can occur, especially in individuals with compromised immune function.

Immune Compromised States:

- Conditions that weaken the immune system, such as diabetes mellitus, HIV/AIDS, cancer undergoing chemotherapy, or chronic steroid use, predispose individuals to infections, including those causing Ludwig’s angina.

Poor Oral Hygiene:

- Inadequate oral hygiene allows bacterial colonization and proliferation in the oral cavity, increasing the risk of developing oral infections that can progress to Ludwig’s angina.

Treatment

Airway Management:

- Airway management is often the first priority in patients with Ludwig’s angina due to the risk of upper airway obstruction from extensive swelling.

- Early assessment of airway patency and consideration of advanced airway management techniques (e.g., intubation, tracheostomy) may be necessary in severe cases or when there is impending airway compromise.

Antibiotic Therapy:

- Prompt initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics is essential to cover the likely polymicrobial infection involving anaerobic and aerobic bacteria.

- Commonly used antibiotics include intravenous penicillin (or ampicillin-sulbactam), clindamycin, or metronidazole to provide coverage against oral flora and anaerobes.

- Antibiotic choice may be adjusted based on local antimicrobial resistance patterns and individual patient factors.

Surgical Intervention:

- Surgical drainage and debridement may be necessary for localized abscesses or to relieve pressure in the submandibular and sublingual spaces.

- Incision and drainage (I&D) under appropriate anesthesia allow evacuation of purulent material and facilitate resolution of infection.

Supportive Care:

- Supportive measures include adequate hydration, pain management, and monitoring for signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or sepsis.

- Close monitoring of vital signs, oxygenation, and fluid balance is crucial, especially in critically ill patients.

Consultation with Specialists:

- Consultation with otolaryngologists (ENT specialists) and infectious disease specialists may be necessary for optimal management, especially in complex cases or when complications arise.

Monitoring and Follow-Up:

- Continuous monitoring of clinical status, response to treatment, and resolution of symptoms is important.

- Follow-up visits ensure complete recovery, assess for any sequelae (such as airway stenosis), and address dental or oral health issues contributing to the initial infection.

Preventive Measures:

- Education regarding oral hygiene practices and regular dental care is essential to prevent recurrent infections.

- Timely management of dental caries, periodontal disease, and other oral infections can reduce the risk of developing Ludwig’s angina.