Inguinal Hernias

content of this page

1- Introduction

2- Anatomical Overview

3- Causes

4- Treatment

Introduction

An inguinal hernia is a common condition characterized by the protrusion of abdominal contents, such as part of the intestine or fatty tissue, through a weak spot or opening in the abdominal wall near the inguinal canal. The inguinal canal is a passageway in the lower abdomen that houses blood vessels, nerves, and, in men, the spermatic cord.

Anatomical Overview

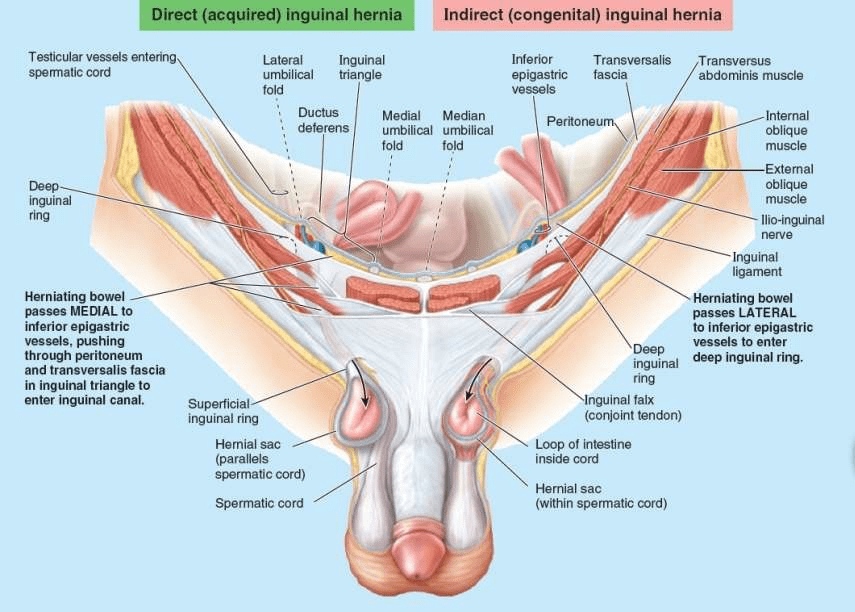

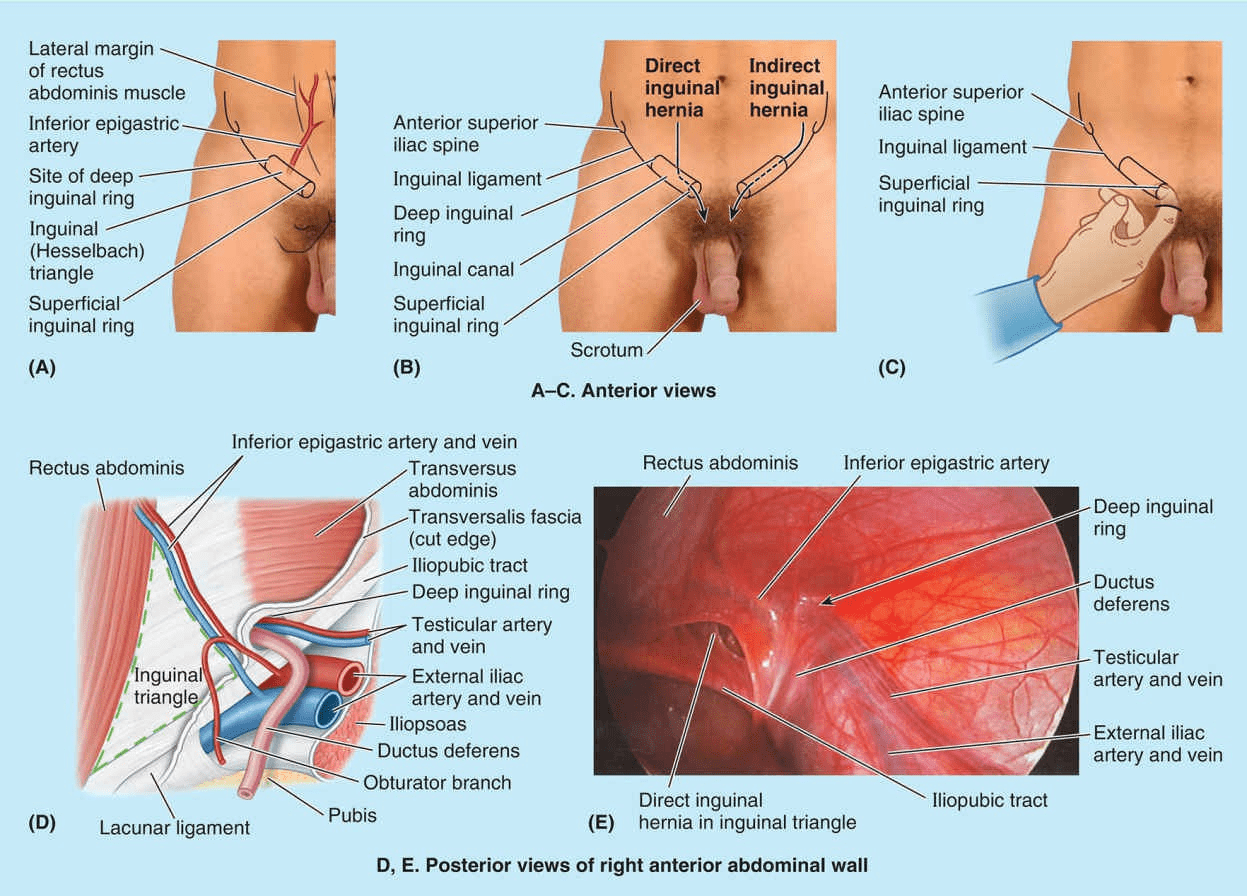

The majority of abdominal hernias occur in the inguinal region. Inguinal hernias account for 75% of abdominal hernias. These herniations occur in both sexes, but most inguinal hernias (approximately 86%) occur in males because of the passage of the spermatic cord through the inguinal canal. An inguinal hernia is a protrusion of parietal peritoneum and viscera, such as the small intestine, through a normal or abnormal opening from the cavity in which they belong. Most hernias are reducible, meaning they can be returned to their normal place in the peritoneal cavity by appropriate manipulation. The two types of inguinal hernia are direct and indirect inguinal hernias. More than two thirds are indirect hernias. Normally, most of the processus vaginalis obliterates before birth, except for the distal part that forms the tunica vaginalis of the testis. The peritoneal part of the hernial sac of an indirect inguinal hernia is formed by the persisting processus vaginalis. If the entire stalk of the processus vaginalis persists, the hernia extends into the scrotum superior to the testis, forming a complete indirect inguinal hernia. The superficial inguinal ring is palpable superolateral to the pubic tubercle by invaginating the skin of the upper scrotum with the index finger. The examiner’s finger follows the spermatic cord superolaterally to the superficial inguinal ring. If the ring is dilated, it may admit the finger without causing pain. Should a hernia be present, a sudden impulse is felt against either the tip or pad of the examining finger when the patient is asked to cough (Swartz, 2014). However, because both inguinal hernia types exit the superficial ring, palpation of an impulse at this site does not discriminate type. With the palmar surface of the finger against the anterior abdominal wall, the deep inguinal ring may be felt as a skin depression superior to the inguinal ligament, 2–4 cm superolateral to the pubic tubercle. Detection of an impulse at the superficial ring and a mass at the site of the deep ring suggests an indirect hernia. Palpation of a direct inguinal hernia is performed by placing the palmar surface of the index and/or middle finger over the inguinal triangle and asking the person to cough or bear down (strain). If a hernia is present, a forceful impulse is felt against the pad of the finger. The finger can also be placed in the superficial inguinal ring; if a direct hernia is present, a sudden impulse is felt medial to the finger when the person coughs or bears down.

Causes

Weakness in the Abdominal Muscles: The abdominal muscles play a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of the abdominal wall. Weakness in these muscles, whether due to genetic factors, aging, or injury, can create openings through which abdominal contents can herniate.

Increased Intra-Abdominal Pressure: Conditions or activities that increase pressure within the abdomen can predispose individuals to inguinal hernias. These may include:

- Heavy Lifting: Repeated or heavy lifting, especially when performed improperly, can strain the abdominal muscles and increase intra-abdominal pressure, leading to herniation.

- Chronic Coughing: Conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), persistent coughs, or frequent sneezing episodes can exert increased pressure on the abdominal wall and contribute to hernia formation.

- Straining During Bowel Movements: Chronic constipation or straining during bowel movements can increase intra-abdominal pressure and weaken the abdominal muscles, increasing the risk of herniation.

- Obesity: Excess body weight can increase pressure within the abdomen and place additional strain on the abdominal muscles, making herniation more likely.

Genetic Factors: There may be a genetic predisposition to inguinal hernias, as they tend to run in families. Inherited factors may influence the strength and integrity of the abdominal wall and increase susceptibility to hernia formation.

Age: The risk of inguinal hernias tends to increase with age, as the abdominal muscles and connective tissues naturally weaken over time. Older adults are more likely to develop hernias than younger individuals.

Previous Abdominal Surgery: Scar tissue from previous abdominal surgeries can weaken the abdominal wall and increase the risk of hernia formation. Inguinal hernias may develop at or near the site of previous surgical incisions.

Gender: Inguinal hernias are much more common in men than in women. This difference is believed to be due to anatomical factors, including the presence of the spermatic cord in men, which creates potential weak spots in the abdominal wall.

Treatment

Hernia Repair Surgery (Herniorrhaphy or Hernioplasty): Surgical repair of an inguinal hernia involves returning the herniated tissue to its proper position within the abdomen and reinforcing the weakened abdominal wall to prevent recurrence. There are several surgical techniques used to repair inguinal hernias, including:

Open Hernia Repair: In this traditional approach, a single incision is made in the groin, and the hernia is repaired through the incision. The surgeon may use sutures to close the defect in the abdominal wall or may reinforce the area with a synthetic mesh.

Laparoscopic Hernia Repair: In laparoscopic hernia repair, small incisions are made in the abdomen, and a laparoscope (a thin, flexible tube with a camera) is inserted to view the internal structures. The surgeon then repairs the hernia using specialized instruments and may place a mesh to reinforce the abdominal wall. Laparoscopic surgery generally offers faster recovery and less post-operative pain compared to open surgery.

Robotic-Assisted Hernia Repair: Robotic-assisted surgery involves using a surgical robot to perform the procedure with greater precision and dexterity. This approach may offer advantages similar to laparoscopic surgery, including smaller incisions and quicker recovery times.

Watchful Waiting (Observation): In some cases, especially if the hernia is small, asymptomatic, or not causing any complications, a healthcare provider may recommend a “watchful waiting” approach. This involves monitoring the hernia over time and opting for surgical repair if symptoms worsen or complications develop.

Non-Surgical Management (Supportive Measures): While surgery is the primary treatment for inguinal hernias, supportive measures may be recommended to manage symptoms or reduce the risk of complications in certain situations. These measures may include:

Wearing a Supportive Device: Wearing a supportive device, such as a hernia belt or truss, may help alleviate discomfort and provide temporary support for the hernia.

Lifestyle Modifications: Making lifestyle changes, such as avoiding heavy lifting, maintaining a healthy weight, and avoiding activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure, may help reduce symptoms and prevent hernia progression.

Emergency Surgery for Complications: Inguinal hernias can sometimes lead to complications such as strangulation (where the blood supply to the herniated tissue is compromised) or incarceration (where the herniated tissue becomes trapped and cannot be reduced). These complications require prompt surgical intervention to prevent tissue damage and restore blood flow.