Acquired Dislocation of The Hip Joint

content of this page

1- Introduction

2- Anatomical Overview

3- Causes

4- Treatment

Introduction

Acquired dislocation of the hip joint refers to the displacement of the ball-and-socket structure of the hip, typically due to traumatic injury or a medical condition. Unlike congenital hip dislocation, which occurs during fetal development or infancy, acquired dislocation occurs later in life, often as a result of significant force or underlying musculoskeletal issues.

Anatomical Overview

Congenital dislocation of the hip joint is common, occurring in approximately 1.5 per 1,000 neonates; it is bilateral in approximately half the cases. Girls are affected at least eight times more often than boys. Dislocation occurs when the femoral head is not properly located in the acetabulum. Inability to abduct the thigh is characteristic of congenital dislocation. In addition, the affected limb appears (and functions as if it is) shorter because the dislocated femoral head is more superior than on the normal side, resulting in a positive Trendelenburg sign (hip appears to drop on one side during walking). Approximately 25% of all cases of arthritis of the hip in adults are the direct result of residual defects from congenital dislocation of the hip.

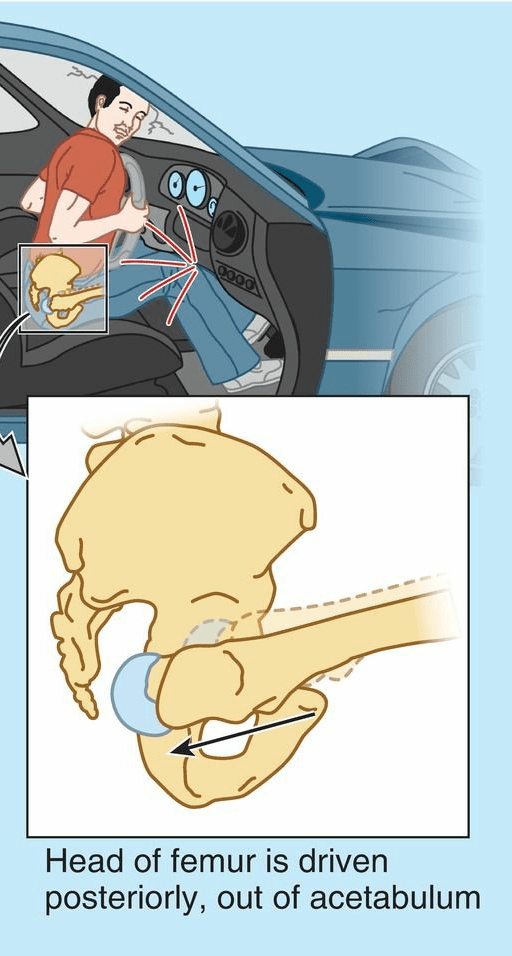

Acquired dislocation of the hip joint is uncommon because this articulation is so strong and stable. Nevertheless, dislocation may occur during an automobile accident when the hip is flexed, adducted, and medially rotated, the usual position of the lower limb when a person is riding in a car.

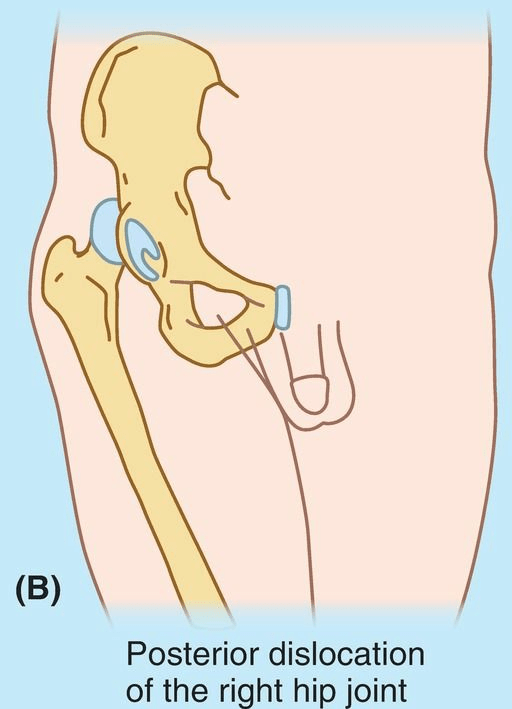

Posterior dislocations of the hip joint are most common. A head-on collision that causes the knee to strike the dashboard may dislocate the hip when the femoral head is forced out of the acetabulum. The joint capsule ruptures inferiorly and posteriorly, allowing the femoral head to pass through the tear in the capsule, and over the posterior margin of the acetabulum onto the lateral surface of the ilium, shortening and medial rotating the limb. Because of the close relationship of the sciatic nerve to the hip joint, it may be injured (stretched and/or compressed) during posterior dislocations or fracture–dislocations of the hip joint. This kind of injury may result in paralysis of the hamstrings and muscles distal to the knee supplied by the sciatic nerve. Sensory changes may also occur in the skin over the posterolateral aspects of the leg and over much of the foot because of injury to sensory branches of the sciatic nerve.

Anterior dislocation of the hip joint results from a violent injury that forces the hip into extension, abduction, and lateral rotation (e.g., catching a ski tip when snow skiing). In these cases, the femoral head is inferior to the acetabulum. Often, the acetabular margin fractures, producing a fracture– dislocation of the hip joint. When the femoral head dislocates, it usually carries the acetabular bone fragment and acetabular labrum with it. These injuries also occur with posterior dislocations.

Causes

Trauma: The most frequent cause of acquired hip dislocation is trauma, such as a motor vehicle accident, fall from a height, or sports injury. These events can exert force on the hip joint that exceeds its normal range of motion, causing the femoral head (ball of the hip joint) to become displaced from the acetabulum (socket).

Hip Fractures: Fractures of the femoral head or acetabulum can disrupt the integrity of the hip joint, leading to instability and potential dislocation.

Sports Injuries: High-impact sports or activities that involve twisting motions or direct blows to the hip can predispose individuals to hip dislocation.

Joint Degeneration: Conditions such as osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis can weaken the hip joint structures over time, increasing the risk of dislocation.

Joint Hyperlaxity: Some individuals have naturally looser ligaments and joint capsules (hyperlaxity), which can predispose them to joint instability and dislocation.

Hip Dysplasia: Abnormal development of the hip joint, known as hip dysplasia, can predispose individuals to hip dislocation later in life.

Surgical Complications: In rare cases, hip dislocation can occur as a complication of hip surgery, such as total hip replacement or hip arthroscopy.

Neurological Disorders: Conditions that affect muscle control and coordination, such as cerebral palsy or stroke, can contribute to hip joint instability and dislocation.

Treatment

Immediate Reduction: The primary goal is to promptly and safely relocate the hip joint back into its socket (acetabulum). This is typically performed under sedation or anesthesia in a hospital setting by a trained healthcare provider. Techniques may include gentle manipulation or traction to guide the femoral head back into place.

Immobilization: After reduction, the hip joint may need to be immobilized with a brace, splint, or traction device to allow the soft tissues around the joint to heal and stabilize.

Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy: Once the hip joint is stable, rehabilitation is crucial to restore strength, flexibility, and range of motion. Physical therapy exercises are designed to strengthen the muscles around the hip joint and improve overall joint stability. A gradual return to weight-bearing activities is typically recommended under the guidance of a physical therapist.

Medication: Pain management with medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or analgesics may be necessary to alleviate discomfort and inflammation associated with the injury.

Surgical Intervention: In some cases, surgical treatment may be required to repair associated fractures, ligament damage, or to reconstruct the joint if there are persistent stability issues. Surgical options may include internal fixation of fractures, soft tissue repair, or even joint reconstruction procedures such as hip arthroplasty (hip replacement surgery).

Long-Term Management: Depending on the severity of the injury and any underlying conditions, long-term monitoring and follow-up may be necessary to assess joint function, address complications such as arthritis or recurrent dislocation, and ensure optimal recovery.

Orthopedic Consultation: Treatment decisions should be made in consultation with an orthopedic surgeon or specialist who can evaluate the specific circumstances of the hip dislocation and recommend the most appropriate course of action.