Gastroparesis

Content of This Page

1- Introduction

2- Causes

3- Symptoms

4- Stages of The Disease

5- Treatment

6- What Should You Avoid

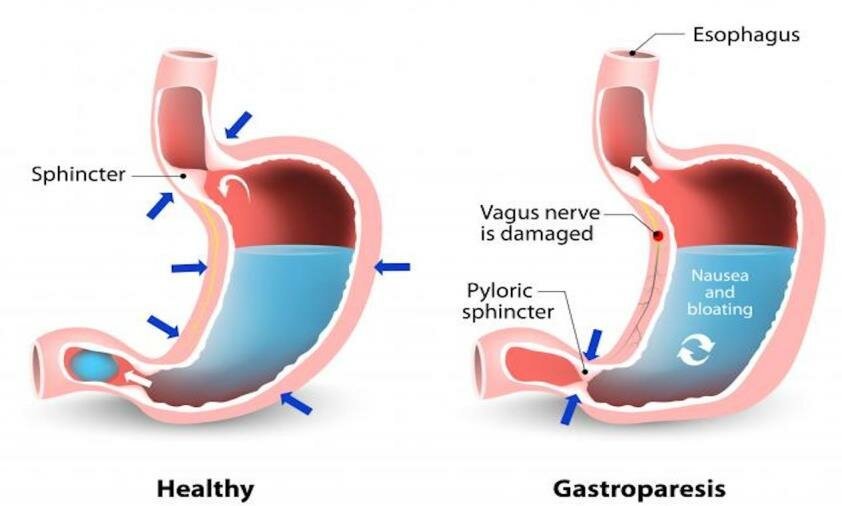

Introduction

Causes

Diabetes: High blood sugar levels can damage the vagus nerve, which controls the stomach muscles, leading to delayed stomach emptying.

Surgery: Procedures involving the stomach or esophagus can damage the vagus nerve or other nerves and muscles involved in gastric motility.

Medications: Certain drugs, such as narcotics, antidepressants, and anticholinergics, can slow down the stomach’s ability to empty its contents.

Viral Infections: Infections like viral gastroenteritis can temporarily or permanently damage the nerves controlling stomach muscles.

Neurological Disorders: Conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or other nervous system disorders can affect the nerves that control the stomach.

Autoimmune Diseases: Some autoimmune conditions can attack the nerves controlling stomach motility.

Idiopathic: In some cases, the cause of gastroparesis is unknown, which is referred to as idiopathic gastroparesis.

Other Conditions: Diseases like scleroderma, hypothyroidism, and amyloidosis can also contribute to the development of gastroparesis.

Symptoms

Nausea: A persistent feeling of queasiness, often occurring after meals.

Vomiting: Vomiting undigested food that has remained in the stomach.

Early Satiety: Feeling full quickly after beginning to eat, even if only a small amount of food has been consumed.

Bloating: A sensation of fullness or swelling in the abdomen.

Abdominal Pain: Discomfort or pain in the upper abdomen.

Loss of Appetite: Reduced desire to eat due to discomfort or feelings of fullness.

Weight Loss: Unintended weight loss as a result of difficulty eating and poor nutrient absorption.

Malnutrition: In severe cases, difficulty absorbing nutrients from food can lead to nutritional deficiencies.

Acid Reflux: Stomach acid can back up into the esophagus, causing heartburn or GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease).

Fluctuating Blood Sugar Levels: In people with diabetes, delayed stomach emptying can make it harder to control blood sugar levels, leading to erratic glucose levels.

Stages of The Disease

1. Mild Gastroparesis:

- Symptoms: Symptoms may be intermittent and mild, such as occasional nausea, bloating, and early satiety.

- Diet: Patients can often manage symptoms with minor dietary adjustments, such as eating smaller, more frequent meals and avoiding high-fat and high-fiber foods.

- Lifestyle Impact: Minimal impact on daily life and overall health.

2. Moderate Gastroparesis:

- Symptoms: Symptoms become more consistent and pronounced, including regular nausea, vomiting, and significant bloating.

- Diet: A more restricted diet may be necessary, focusing on easily digestible foods and possibly using liquid nutrition supplements.

- Medication: Patients may require medications to help stimulate stomach motility and control symptoms like nausea and vomiting.

- Lifestyle Impact: More noticeable impact on daily life, with potential weight loss and nutritional deficiencies starting to emerge.

3. Severe Gastroparesis:

- Symptoms: Persistent and severe symptoms, including frequent vomiting, severe abdominal pain, and an inability to tolerate solid food.

- Diet: A highly restricted or liquid-only diet may be necessary. In some cases, enteral nutrition (feeding through a tube) or parenteral nutrition (intravenous feeding) may be required.

- Medical Intervention: Frequent medical interventions, such as hospitalizations for dehydration or malnutrition, may be needed. More invasive treatments, like gastric electrical stimulation or surgery, might be considered.

- Lifestyle Impact: Significant impact on quality of life, with potential for serious complications, including malnutrition, weight loss, and blood sugar management issues.

4. Refractory Gastroparesis (sometimes considered an advanced or severe stage):

- Symptoms: Symptoms are resistant to standard treatments and severely impact daily functioning.

- Treatment: Requires advanced medical management, often including experimental therapies, and is typically associated with a high level of disability.

Treatment

1. Dietary Modifications:

- Smaller, Frequent Meals: Eating smaller meals more often can help reduce the feeling of fullness and ease digestion.

- Low-Fat, Low-Fiber Diet: Fat and fiber slow down stomach emptying, so a diet low in these components can help. Soft or liquid foods may be easier to digest.

- Pureed or Liquid Diet: In more severe cases, pureed or liquid meals may be necessary to ensure proper nutrition while reducing symptoms.

2. Medications:

- Prokinetic Agents: These drugs, such as metoclopramide or erythromycin, stimulate stomach muscle contractions to improve gastric emptying.

- Anti-Nausea Medications: Medications like ondansetron or promethazine can help control nausea and vomiting.

- Pain Management: For those experiencing abdominal pain, medications like low-dose tricyclic antidepressants may be used, though they must be chosen carefully as some pain medications can worsen gastroparesis.

3. Blood Sugar Control:

- For Diabetics: Tight blood sugar control is essential as high blood sugar can worsen gastroparesis. Adjustments to insulin or other diabetes medications may be necessary to stabilize glucose levels.

4. Gastric Electrical Stimulation:

- Device Therapy: In some cases, a gastric pacemaker (Enterra Therapy) may be implanted to send electrical impulses to the stomach muscles, helping to reduce nausea and vomiting. This is typically reserved for severe cases that do not respond to other treatments.

5. Endoscopic or Surgical Interventions:

- Endoscopic Therapies: Procedures like botulinum toxin (Botox) injections into the pyloric sphincter or endoscopic pyloromyotomy can help relax the stomach’s exit to improve emptying.

- Surgery: In severe, refractory cases, surgical options such as a pyloroplasty (widening of the pyloric sphincter) or a jejunostomy (feeding tube directly into the small intestine) may be considered.

6. Nutritional Support:

- Enteral Nutrition: If oral intake is insufficient, a feeding tube may be placed to deliver nutrition directly to the small intestine, bypassing the stomach.

- Parenteral Nutrition: In extreme cases, where even enteral feeding is not possible, intravenous nutrition (parenteral nutrition) may be necessary.

7. Lifestyle Adjustments:

- Physical Activity: Light physical activity after meals can help stimulate digestion.

- Stress Management: Stress can exacerbate symptoms, so relaxation techniques and stress management may be beneficial.

8. Management of Underlying Conditions:

- Addressing Root Causes: If gastroparesis is secondary to another condition (e.g., diabetes, hypothyroidism), treating the underlying cause is crucial.

What Should You Avoid

1. Foods to Avoid:

- High-Fat Foods: Fat slows down stomach emptying, so it’s best to avoid fatty meats, fried foods, creamy sauces, and high-fat dairy products.

- High-Fiber Foods: Fiber can be difficult to digest and may cause blockages. Avoid raw vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds, legumes, and high-fiber fruits like apples, berries, and oranges.

- Tough Meats: Foods that are difficult to chew and digest, such as steak or pork, should be avoided. Instead, opt for tender or ground meats.

- Carbonated Beverages: These can cause bloating and discomfort, so it’s better to avoid sodas and sparkling water.

- Alcohol: Alcohol can slow down gastric emptying and irritate the stomach lining, so it’s best to avoid it or consume it in very limited quantities.

- Spicy Foods: Spicy foods can irritate the stomach lining and exacerbate symptoms.

- Acidic Foods: Foods like tomatoes and citrus fruits can increase acid reflux and may worsen symptoms for some individuals.

2. Eating Habits to Avoid:

- Large Meals: Large meals can overwhelm the stomach and exacerbate symptoms. It’s better to eat smaller, more frequent meals.

- Eating Too Quickly: Eating quickly can lead to swallowing air, which may cause bloating and discomfort. Chewing food thoroughly and eating slowly can help.

- Eating Before Bed: Avoid eating within two to three hours before lying down or going to bed, as this can lead to worsening symptoms and acid reflux.

3. Medications to Avoid:

- Narcotics (Opioids): These can slow down the digestive system and worsen gastroparesis symptoms.

- Anticholinergic Medications: Drugs that block the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (such as certain antihistamines and antidepressants) can reduce stomach motility.

- Certain Diabetes Medications: Some diabetes medications, like GLP-1 receptor agonists, can slow gastric emptying. It’s important to discuss these with your healthcare provider if you have diabetes and gastroparesis.

4. Lifestyle Factors to Avoid:

- Sedentary Lifestyle: Lack of physical activity can slow digestion, so staying active with gentle exercise, such as walking, can help.

- High Levels of Stress: Stress can exacerbate symptoms, so it’s important to manage stress through relaxation techniques or other stress-reducing activities.